By Paul Miles

This is part three of a three part series on Bible translation. The first part of the series was an introduction to manuscripts and how strikingly precise they are. In the second part of the series, we saw a brief history of some early Bible translations. I hope you've had the opportunity to look further into these two fascinating topics on your own. This post is the conclusion of the series and will consider some basics of translation philosophy and will have some short reviews of a few popular English Bible translations.

As mentioned earlier, the manuscripts that Bible translators use are reliable and still carry the meaning of the original authors. The translators themselves tend to cause more difference between the English texts that we hold in our hands than the manuscript variants do. Usually, even between textual variants and translator differences, the translations carry pretty much the same meaning. This isn't always the case, but there are some things we can be aware of to verify our text and translations to make sure that our Bible studies are of the highest quality. A good Bible translation objectively translates the Word and reads as little extra meaning into the text as possible. The meaning that the translators bring to the text depends on many factors, two of which are the translators' theological presuppositions and their philosophy of translation.

Theological Presuppositions

Sometimes translators will translate a Bible that carries a different meaning because of a theological presupposition. One extreme example is a new Bible translation called the Queen James Bible. According to the Queen James Bible website, "Homosexuality was first mentioned in the Bible in 1946 in the Revised Standard Version. There is no mention of or reference to homosexuality in any Bible prior to this - only interpretations have been made." This view is clearly off, but it changes the way that the translators do their job. The Queen James Bible is basically the King James Version, but the translators changed a few verses to make the Bible more gay-friendly. Another example results from the Jehovah's Witness' rejection of the Trinity. To avoid the orthodox translation of kai theos en ho logos ("and the Word was God") and other key verses, they have published the New World Translation, which renders the end of John 1:1, "and the Word was a god." The first thing to consider when choosing a Bible translation is who the translators are. What is their theological background? Also, why are they translating? There are plenty of good English Bible translations out there, so why do we need another? If the reason for a new translation is to make the Bible promote homosexuality or hide the doctrine of the Trinity, then the translation is better left on the bookshelf.

Philosophy of Translation

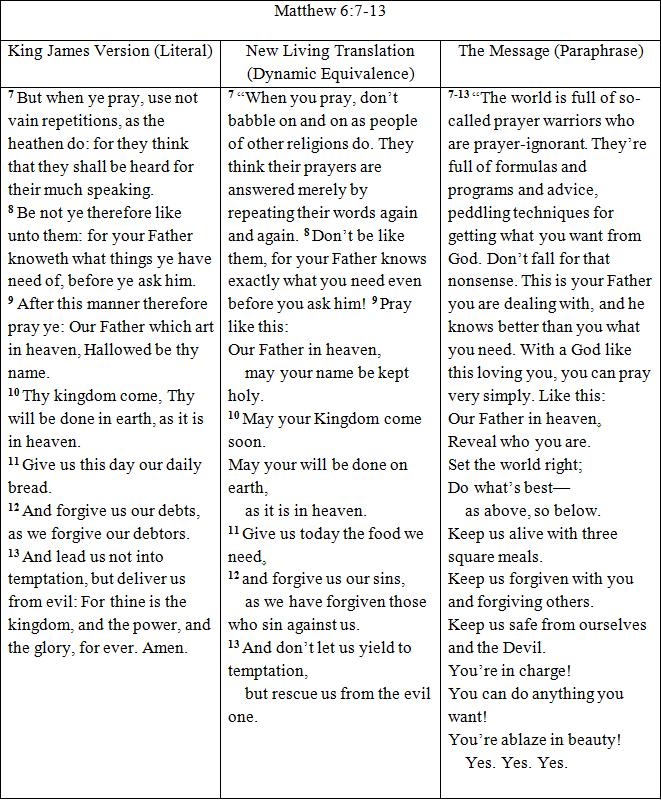

Another factor in how a translation turns out is the translators' philosophy of translation. The three basic translation philosophies are literal, dynamic equivalence, and paraphrase. Let's consider a passage translated with the three different approaches:

Quite a few differences, right? Where one version renders heathen, another renders prayer warriors. Where one translation has "after this manner therefore pray ye," another has "pray like this." Where one reads "and don't let us yield to temptation," another reads "keep us safe from ourselves." Not all translations clearly fall into one philosophical category, but many fall somewhere between two of the approaches. Let's take a look at the three basic philosophies and then we'll rate some of today's popular Bible translations.

Literal

Literal Bible translations seek to preserve the original text as closely as possible in the translation. The downside of this approach is that sometimes a literal translation doesn't catch the full meaning of phrases or idioms in the original languages, and sometimes leaves the audience with an English sentence that is difficult to read or has awkward wording. The upside is that if a translator takes a more literal approach, then he is less likely to transfer his own opinions into the text. As Leland Ryken puts it, "An essentially literal translation operates on the premise that a translator is a steward of what someone else has written, not an editor and exegete who needs to explain or correct what someone else has written."

Dynamic Equivalence

Dynamic Equivalence Bibles are translated thought-by-thought. The goal is to provide the same dynamic impact of the Scriptures that the original text carries but is lost when translated directly. There are a few problems with this approach, but perhaps the most disturbing is that the translation is being driven by the meaning that the translator gets from the text. The Word of God as the Dynamic Equivalence readers see it is basically at the mercy of fallen translators' theological presuppositions. The advantage is that dynamic equivalence can make understanding the Bible easier, but at what cost? Even if the translators are working with good presuppositions, they are still using a rather poor method of translation.

Paraphrase

Paraphrases are basically modern authors re-telling the Bible in their own words. Sometimes they are entertaining, but they really don't relay the Biblical text to the reader. For example, in his extreme paraphrase, The Word on the Street, Rob Lacey 'translates' Genesis 1:1, "First off, nothing. No light, no time, no substance, no matter. Second off, God starts it all up and WHAP! Stuff everywhere!" This is not the Bible; this is a man telling his version of the creation account. Often paraphrases don't claim to be the Bible. In fact, on the copyright page of The Word on the Street, we can read, "Rob Lacey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work," and rightly so. God wrote the Bible and men write paraphrases. A Christian does his spiritual journey a huge disservice if he replaces an actual Bible translation with a paraphrase. That being said, paraphrases aren't completely bad. They give insight to how the author understands what the Author has written. Just like any commentary, though, a paraphrase is only helpful as a supplement to a Bible.

Review of Popular Translations

As a conclusion to this series, I would like to propose some quick reviews of a few popular English translations that are in use today. I'll be using my finely tuned five-point scale to rate the King James Version, the New King James Version, New American Standard, New International Version, and The Message. But please remember that this is only one man's opinion and that you should do your own research when you consider which Bible to read. I would encourage you to look into some additional Bible translations and even to compare different translations side-by-side in your own Bible studies.

King James Version

The King James Version is a classic. It has gone under several revisions over the centuries, but 1611 editions made a small comeback a few years ago to celebrate the King James Version's 400th anniversary. King James uses archaic English pronouns such as "thou" and "ye," which are actually closer to the original grammar, but sometimes cause a stumbling block to modern readers.

Year Published: 1611

Greek Text: Textus Receptus

Translation Philosophy: Literal

Rating: 4 out of 5 William Tyndales

New King James

The New King James is a conservative revision of the King James Version. It uses the same manuscripts and similar phrasing, but with an updated vocabulary that is more palatable for modern audiences.

Year Published: 1982

Greek Text: Textus Receptus

Translation Philosophy: Literal

Rating: 4.5 out of 5 William Tyndales

New American Standard

The New American Standard is a revision of the American Standard Bible of 1901, which is another fine translation. Like the New King James, it does away with "ye" and "thou" and uses a more comfortable vocabulary while still rendering a literal translation.

Year Published: 1971

Greek Text: Novum Testamentum Graece

Translation Philosophy: Literal

Rating: 4.5 out of 5 William Tyndales

New International Version

Of the dynamic equivalence translations, the New International Version is one of the more literal. It is the most popular English translation today, but carries an unfortunate burden of reformed theology. It may not be as accurate as the earlier mentioned translations, but with its popularity it shouldn't be ignored.

Year Published: 1978

Greek Text: Novum Testamentum Graece

Translation Philosophy: Dynamic Equivalence

Rating: 2 out of 5 William Tyndales

The Message

Eugene Peterson, the translator of The Message has said, "One of the Devil's finest pieces of work is getting people to spend three nights a week in Bible studies [...] Well, why do people spend so much time studying the Bible? How much do you need to know?" The Message is a fine resource for propping open a window on a sunny day, but when it comes to Bible study, it's best left on the shelf.

Year Published: 2002

Greek Text: Multiple

Translation Philosophy: Paraphrase

Rating: 0.25 out of 5 William Tyndales